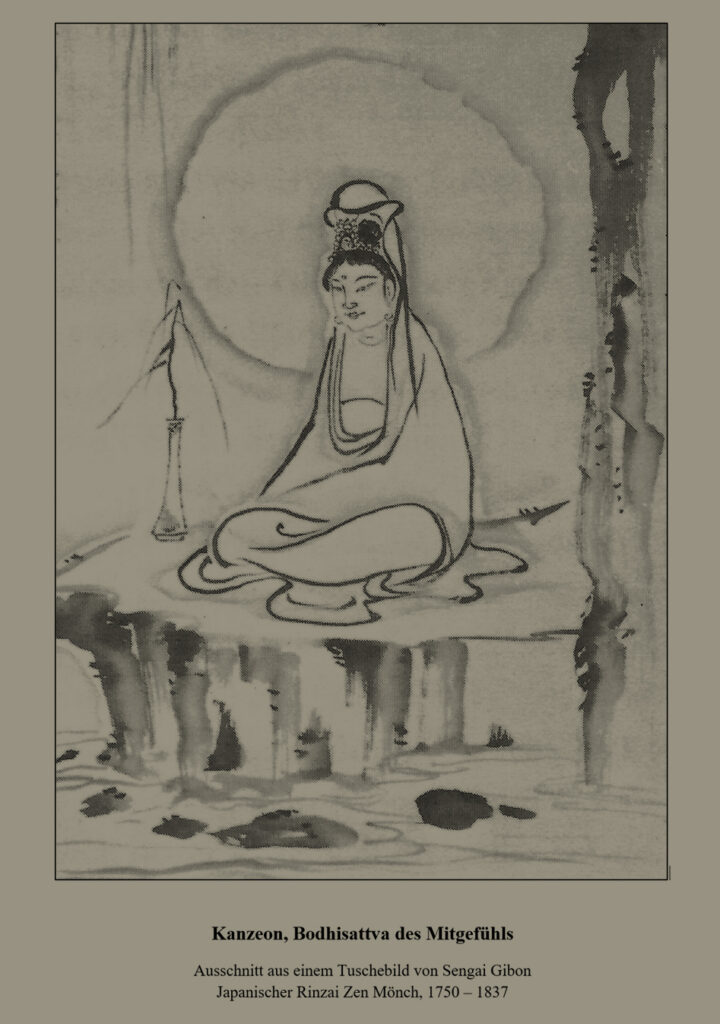

This universal vow is the vow which the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara made, acting as representative of all Bodhisattvas. We are told of this in chapter 7 of the Lotus Sutra. The term Bodhisattva means “Enlightened Being”. Avalokiteshvara (Sanskrit) is better known to us as Kanzeon, Kannon, or Kwannon in Japanese, or also as Kuan Yin in Chinese. This being is known as the Bodhisattva of compassion. He hears the sound of the world, that is to say the sighs of the beings that are suffering, and he reacts to them. In the course of the Buddhist history this figure has changed it’s gender a few times; was temporarily depicted as woman and then again as man, or without explicit gender features. It is not a historical being that once really lived.

With this vow he made, Avalokiteshvara committed himself on not entering Nirvana, on renouncing the final liberation of reincarnations, as well as reaching Buddhahood until all sentient beings are led to liberation from suffering. This fundamental attitude is the great ideal in the Mahayana Buddhisme, to which also our Zen school belongs. By way of contrast the Hinayana Buddhisme, also called Theravada Buddhisme, emphasizes the individual liberation, the personal entering of Nirvana.

Each time when we start Zazen at our Dojo we recite the Heart Sutra, the Great Light Dharani, and at the end the Four Great Vows:

However innumerable all beings are, we vow to save them all

However inexhaustible delusions are, we vow to extinguish them all

However immeasurable Dharma teachings are, we vow to master them all

However endless the Buddha’s way is, we vow to follow it

These Four Great Vows are in their meaning identical with Avalokiteshvara’s vow. They are adapted to the feeling of us practicing humans to be still far away of Buddhahood. Out of this feeling, and being honest, it seems to us completely impossible to fulfill these vows. Nevertheless we repeat them over and over again. They are none other than the complete expression of our intrinsic Buddhanature. Whenever we recite these vows wholeheartedly, and decide to try to fulfill them as best as we can, at this moment we are none other than Buddha. To live this attitude, no matter what happens, without if, or when, means to be liberated from suffering, to be liberated from separation. This attitude lets us dissolve into the whole, lets us overcome the narrow and limited views of the individual and egoistic being. Exactly in this lies the immeasurable depth of these vows which we recite again and again. May our compassion extend over the whole universe and become deep as the ocean.

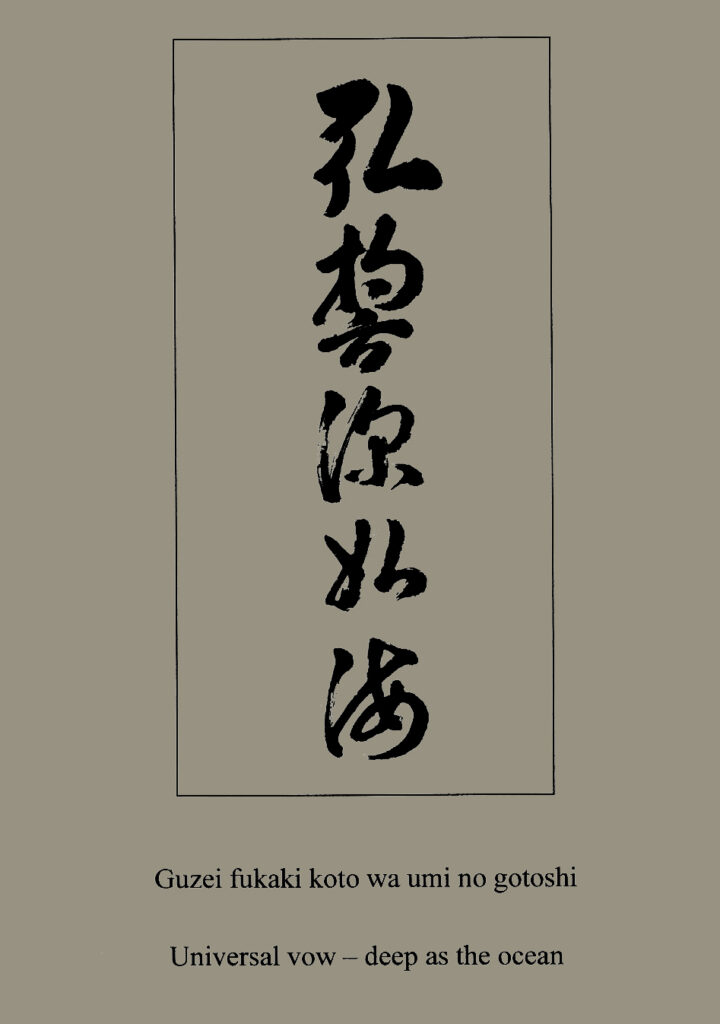

Konnichi wa – that’s how Japanese people greet each other in everyday language. Literally translated it means “Today”, or “This day”, and is equivalent to our Good Day or Hello. So Konnichi means today.

The expression “Buji” is much more difficult to translate. It is a combination of “Bu”, which means no, nothing, not, and is a synonym to our “Mu” and to the Chinese “Wu”. And “Ji” means activity, event, to do, to want and to exist. So Buji means: Nothing to do, no duty, nothing to attain, no wanting, or “No Doing”, like the Chinese Wu Wei. Here in the West Wu Wei is known from the Asian martial arts, like Kung Fu, Wing Tsun and Wushu, and also from Tai Chi and Qi Gong. To keep it simple I will write in the following text of No Doing.

In Konfucianisme and Taoisme in ancient China, as well as beyond, in all East-Asian culture, this No Doing was regarded to be a recommended attitude, or quality, of people with great responsibilities such as kings or emperors. In the Tao Te King appears this saying: “With No Doing, nothing remains undone.” We feel already that this No Doing does not at all mean that we should spend the day without moving in bed or on the couch. But if we can, without having any intention, without pursuing any goal, without wanting anything, just be aware of the present moment, then we can perceive what needs to be done right now. Have we finished the meal, the dishes are waiting to be washed. Is there a little or a big human child crying, it wants to be comforted. When dust has settled, we should clean. The founder of our Zen school, Rinzai Gigen Zenji Dai Osho, who passed away around 867 in ancient China, once said in one of his talks:

“As to Buddha Dharma, no artificial effort is necessary. Just be natural, don’t strive. Shitting, pissing, putting on clothes, eating food, and lying down when you are tired. Fools may laugh at me, but the wise understand.”

This attitude of No doing stands in sharp contrast to the values that are honored within our society. From early childhood on we are told to pursue goals, to educate and optimize ourselves, to make “something” out of our lives, to attain material wealth and to be esteemed by the society. And through all this striving we lose ourselves and become separated from our inner source. Not that we really could separate from it. It brings us forth all the time and is ever present within us as the primary origin. But we lose sight of it, lose our connection with it and become unaware of our origin. This “making something out of our lives” is like putting legs to a snake, or like putting another hat on our hat. Where then do we come from? Are we not completely and fully alive as we are? Can a blade of grass, can the sun, can a rose make more out of itself? Because they are 100% what they are, through this fact they are unique, unrepeatable and wonderful. It is a great mistake to think that with us humans it is a different story. Were not all of us born all by itself? Didn’t we grow up all by itself, developed from baby to child, from child to teenager, from teenager to adult, without being able to do anything toward or against it? Are we not, as diverse and imperfect as we are, absolutely complete and perfect? Why have we lost confidence in this incomprehensible, not understandable something, or better nothing (MU), which creates us, the world, and the boundless universe with unfathomable wisdom.

Only a human, who has emptied himself of all inner noise, of all wanting, of all judgment, attainment and avoidance, can wholeheartedly react to the world. Had Kanzeon, the Bodhisattva of compassion, an inner agenda, a plan, or an intension to help all sentient beings in their suffering – never ever would he be able to hear their sighing and to spontaneously react out of his compassion. Indeed – only with No Doing nothing remains undone.

To conclude I would like to point out the spontaneous, lighthearted easiness and elegance with which the artist wrote this calligraphy, completely in harmony with the meaning of the words.

This quotation is part of a sentence that supposedly Confucius himself had said around 290 before Christ in ancient China: “The way is near, but we seek it far away; the work is easy, but we seek the difficulties.”

The Way, Dao in Chinese, Dô in Japanese, can be interpreted in different ways. Most commonly it is understood to be the Way from A to B along the edge of the forest, or through the gauge or so. It also bears the meaning of the course of our life on which we are on the Way. Any proceeding development can be understood as Way. And so our Zen practice, our training is also called Way. The word Dôjo is composed of Dô = Way, and Jo = place; so the Dôjo is the location where practice takes place. This applies not only for places where Zen is practiced, but also for some other Ways of practice, especially Far Eastern martial arts like Judo, Karate and Aikido. Also we often use the word Zendo, which is an abbreviation of Zen Dôjo.

So, this Way of ours is supposed to be near. We don’t need to seek it far away. We don’t need to fly to Japan to practice Zen. Most likely we can easily agree to this. But Zen has put the words of Confucius even more concretely and says: The Way lies under your feet! Wherever we are, whatever we do, it is none other than the Way, our Way, our development, our proceeding, our practice. We don’t need to fly to Japan, not even to travel to the Dôjo, not even to leave the house.

If we look from this fundamental point of view, all humans, in a even deeper sense all manifestations, are on the Way, ceaselessly developing and changing. If we ask about the goal of this Way, in other words, if we look for the goal in a distance, we go wrong. Not anywhere else than where we are at the time the Way fulfills itself every moment. Have we returned to the origin and source of our being, we are completely at home and present in the Here and Now. Then we experience what is described in the Zen story “The bull and the herdsman” at the ninth step, the one before the last.:

“Already the herdsman has spent all the powers of his heart and went all the Ways to the end.

Even the clearest awakening does not surpass being blind and deaf.

The way which he had come, ended under his straw sandals.

No bird sings. Red flowers bloom in splendid confusion.”

Translated quotation from the book: Der Ochs und sein Hirte, Günther Neske Verlag

Being blind and deaf, which are praised here, of course do not mean the ordinary way of not being able to see and hear. They mean to be freed of the greed for gain and the fear of loss, to be freed from the opinions about Good and Bad that stand up against each other like spears on the battlefield. Or even more essentially: Buji – No doing! If we are not there yet, we have to spend all might of our heart, have to practice, have to search around, have to come to the Dôjo to practice with the others, and maybe even have to fly to Japan, until the endless Way ends under our feet, until we arrive at where we are right now.

This expression “Chisoku” is of utmost importance in Zen. It is composed of two Kanji (Chinese characters), which we can clearly see in this calligraphy. The character above to the right is Chi = knowledge, or to know; and the lower one on the left side is Soku = enough, sufficient. So, the meaning is to know that there is enough. There is enough of everything, sufficient, more than sufficient, more than enough. The statement of this fact goes completely against our endless human discontentment. If things would go according to this discontentment, it would never be enough. Even when we have achieved what we had wished for, the next wish follows immediately, and we want more and something better.

This attitude of modesty, like so much in Zen can be traced back to the ancient Daoism in China. In the Tao Te Ching the word Zhisu, Chinese for Chisoku, appears two times, namely in the chapters 33 and 44. I quote from Stephen Mitchell’s translation of the Tao Te Ching into English:

“If you realize that you have enough (Chisoku), you are truly rich.”

“Be content with what you have (Chisoku), rejoice in the way things are.

When you realize there is nothing lacking, the whole world belongs to you.”

When we hear that there is enough of everything, we may think mainly of food, money, space to live, of friends, of things that we need and have to make efforts to get. But how about illnesses, limitations, boredom, pain, whether physical or emotional, hunger, loneliness and all those things that we feel we don’t need, that we feel we could live without. Our selfishness, our egoism strictly holds on to the opinion that we only need those features which are pleasant and which grant our survival. Because our egoism obscures and fogs our view, we have great difficulties to realize that nothing in this universe is superfluous, that everything is needed and has its purpose, which may be hidden from our understanding. If we scale down all our pretensions, all our claims toward life to Zero, only then we can realize and experience that there is enough of everything. Only then we can gratefully accept life – exactly as it is – as a gift.

This calligraphy is written freely. Below I added the print version of it so that we can see how the calligrapher converted the classical Ideograms into a dynamic, lively and intuitively written piece of art. The one stroke to the right means One – Ichi in Japanese. And Nyo means absolute, or the absolute; like in the dedication to the Heart Sutra: Buddha Shakyamuni Nyorai. So, we could translate this calligraphy literally and awkwardly as: One Absolute. But this Absolute is so absolute, that it cannot be One, even less Two. It is indefinite, that is to say without beginning, without an end, pervading everything, not graspable, timeless, everlasting, not existing, and yet it brings forth all forms. In Zen we call it Mu.

But enough now with this intellectual smarty talk. How can we arrive at being completely dissolved in this absolute, at feeling One with it. In our Koan training we are told to become one with the Koan, with the situation that appears in it, in order to find a solution to it. And in our everyday life as well we are advised to become one with the circumstances in order to be able to react adequately. And sometimes, only all to seldom, there are these moments in our lives when „everything is all right“, as we might say. These are moments in which there is no inner resistance against the circumstances, as they are right at that moment. Moments in which we can leave ourselves to the situation, without being intoxicated; in which we are carried by life, in accordance with the universe, and are aware with a sense of happiness, that everything is as it is. But if there stirs the slightest critical thought, the tiniest discontentment, even just with ourselves, this state is lost, and we find ourselves again in the well known feeling of „not yet“, paradise is still far away. Usually we see the cause of this in the circumstances not being as they should be, or in ourselves not being so advanced in our development as we hoped for. After years of practice, of Zen training, we become aware of the fact, that it is not the circumstances that hinder us from being one with. As long as we try to bend the circumstances to our likes, as long we are battling them, and therefore separated from them. Only when we have given up trying to change the world can we become one with it, can we accept and enjoy it as it is. This inner attitude is often seen as fatalistic and therefore gets criticized. But this critic is very superficial and shallow. When we accept the circumstances as they are right now, that does not mean that we cannot be active and change whatever needs to be changed. Let’s say we sit at the table after a nice dinner and we notice the dishes, dirty as they are, still standing on the table. We can talk about them, or be annoyed, discuss how we could avoid this, or even try to find the guilty person who would have to clean them. But we also could simply accept them, become one with them, and as a natural response could bring the dishes to the kitchen and wash them. What might be easy for us with the dishes, can be quite difficult in other situations. Our stubborn self-will is almost limitless. The conviction that we are entitled to have the universe, the world, the circumstances, as well as ourselves as we like it is hard to uproot. To extinguish the base of this egoism is our practice. It cannot be done in an instance. To drill and grind patiently is necessary. Repetition, repetition, repetition, and again and again the change between Zazen, Sesshin and our everyday life, in which our contemplation and insight has to be proven, are our never ending practice on the way.

Once our self-will has ceased, once we have died the great death, once immersed into the absolute, we share the experience of the herdsman taming the ox on the next to last step of his development:

Done is what had to be done, and all ways are completed.

Clearest awakening does not differ from being blind and deaf.

The way he once came has ended under his straw sandals.

No bird sings. Red flowers bloom in glorious splendor.

Great courage is necessary to become like dead ashes, to die once the great death. But only so we can become aware of the absolute, immerse in it, become one with it. To a certain degree we can intellectually understand the meaning of these words. The exhausting practice and the experience, our own becoming One, are of a completely different existentially shattering power. Finally arrived at home, there is nothing left to do. Wondrously life lives itself.

Death and life – not one not two;

sun, moon and stars;

trees, grasses and flowers;

mountains, valleys and rivers;

humans, animals and viruses;

All are blessed

When it comes to such mystical figures like Kanzeon, or the Holy Mary, or Jesus, and many others, we human beings have a tendency to worship them with offerings, incense, prayers and dedications. We hope and wish that some of their divine goodness shall manifest itself in the world, or even that a little bit of it may be transferred upon us. These rituals are as old as humanity, and are beautiful as such.

And yet – when we contemplate with intense effort on where we come from, who we really are, we realize that That, which creates us – and everything – is none other than our own true being. That Something, which brings about that we get born, that our heart beats, our liver functions and our hair grows, which lets us breathe whether we are awake or asleep, and which lets us die when time has come, – that Something is none other than the all-embracing compassion – far beyond pity, charity, readiness to help and improvement of the world. From the beginningless beginning it is present and works. All we have to do is to let it work.